Disclaimer

LWS Financial Research is NOT a financial advisory service, nor is its author qualified to offer such services.

All content on this website and publications, as well as all communications from the author, are for educational and entertainment purposes only and under no circumstances, express or implied, should be considered financial, legal, or any other type of advice. Each individual should carry out their own analysis and make their own investment decisions.

In this deep dive, we will analyze Goehring & Rozencwajg’s Q2 2025 commentary, an American investment firm specialized in commodities, known for its consistently insightful and contrarian views. In this case, they provide an analysis of the current macro environment and explain why oil is one of the most attractive market niches today. This idea aligns perfectly with our shared outlook on the imminent commodity bull market, which combines a macro approach similar to that of G&R. What is shared in this article, although written in the first person, reflects G&R’s research and opinion, not that of LWS Financial Research.

The inflationary surge about to begin

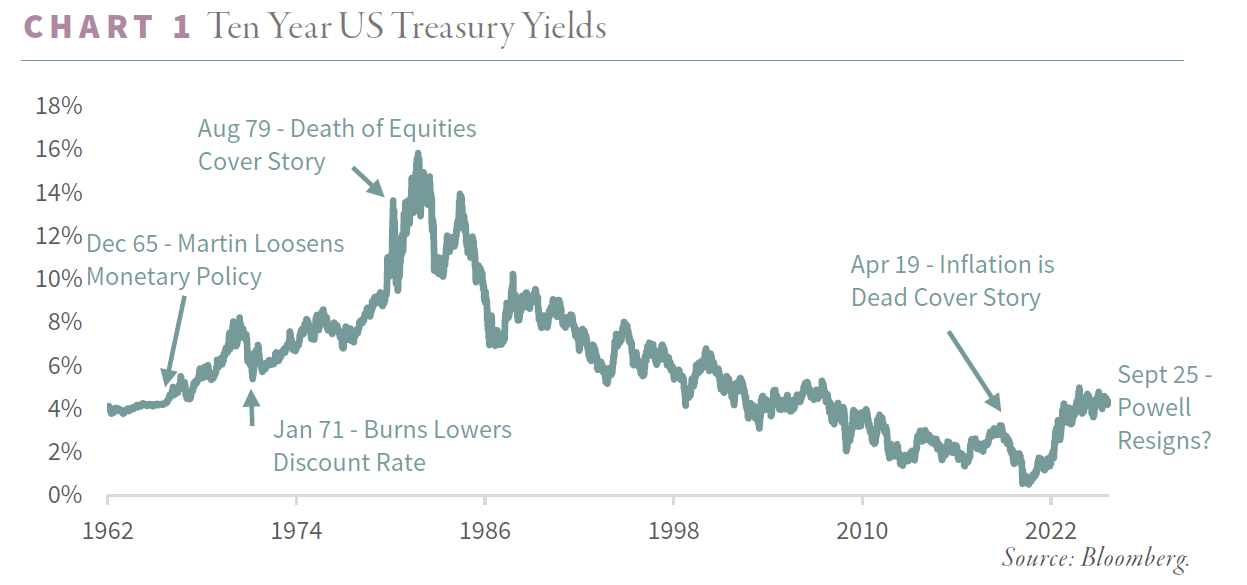

In the 1970s, the Federal Reserve eventually gave in to political and social pressure. Concessions became the fuel for an inflationary spiral that devoured almost everything… except commodities. Natural resource stocks were among the few shelters that survived the blaze. Half a century later, the parallel is uncomfortable. Jerome Powell now finds himself at a similar crossroads. He can cut rates directly, or step aside to let someone else more willing do it. The practical outcome would be the same: reigniting the inflationary fuse.

The narrative of the “great disinflation” launched by Volcker—four decades of falling yields and subdued price pressures—is exhausted. The cycle has changed. What lies ahead is not stability, but a long-lasting inflationary regime, with dynamics far more persistent than most analysts and fund managers are willing to acknowledge. History doesn’t repeat, but it often rhymes in the essentials. And if the 1970s taught us anything, it is that when inflation comes back to stay, the assets that work are not the usual ones.

For many investors, the inflationary episode of 2021 is already closed history. The dominant story is one of normalization, the return of price stability, as if it were an old friend back for good. The euphoria in long-duration assets—led by big tech—reflects that complacency in its purest form. But history is usually less forgiving than market narratives. Academic consensus is clear: the great inflation of the 1970s did not begin in 1973 with the oil embargo, but much earlier. The seeds were sown in the 1960s. The decisive blow came in 1972, when Arthur Burns yielded to political pressure, cut rates, and opened the monetary spigot just before the collapse of Bretton Woods. The result was immediate: inflation hit 7% within a year, and 12% after the energy shock.

What is unsettling is how familiar this all sounds. The pressure Powell faces today is no different in essence, even if the channels have changed. Then it was private meetings, strategic press leaks, and calls from the White House. Today it’s press conferences, social media, and direct messaging to voters. But the objective is the same: to force the Fed’s hand, even if it compromises long-term stability. Current complacency overlooks that historical lesson. Inflation is not a fleeting scare, but a long cycle. And when monetary policy becomes a hostage to political pressure, the story does not end with a “soft landing.” It usually ends in flames.

Markets, like social life, also have fashions. There are martini seasons and Manhattan seasons; growth stock seasons and commodity seasons. In recent years, we have been fully immersed in the carry trade season. The term sounds technical, but its logic is simple: borrow cheap, bet that nothing breaks, and lend long. A massive, leveraged position against volatility. As long as the market stays docile, flows feed on themselves: more calm generates more carry, more carry attracts more money, and so on—until someone switches on the lights and everyone realizes the party wasn’t free.

This regime has always favored the same assets: technology, growth, credit. Everything that thrives under apparent stability. And it has punished everything else: natural resources, energy, metals. The question is what happens when the paradigm shifts. What if the narrative of perpetual calm breaks down, and energy and commodity prices return to center stage? It wouldn’t be the first time the market discovers, with some surprise, that the glamour is not in Silicon Valley, but in a barrel of oil or a ton of copper.

Oil’s resurgence

Few commodities generate as much rejection today as oil. For many investors it is a relic of another era, a “toxic asset” in a world obsessed with the energy transition. But precisely for that reason, we believe it could become the best performer of the next five years—perhaps even of the decade. The dynamic is familiar. In every major bear market, the narrative hardens into dogma. Prices fall, a “definitive” explanation takes hold, and gradually conviction builds that the asset no longer has a place in the future. Until fundamentals prove the consensus wrong.

It’s not the first time this has happened. In the 1990s, the pariah was not oil but gold. After Nixon closed the Treasury window in 1971 and with a world fully monetized in paper, central banks rushed to sell reserves. The yellow metal was considered a deadweight compared to bonds. Panic selling set in, with massive liquidations and even an informal pact in Washington to prevent sales from becoming too embarrassing. The price collapsed 70% in two decades, bottoming at $252 in 1999. Unwittingly, the market was giving gold away. At several points between 2000 and 2003, one ounce traded for barely seven barrels of crude—the lowest ratio in history. In hindsight, it was nonsensical. Today, oil occupies that place in financial imagination. And history suggests that when an asset reaches that level of contempt, it is on the verge of flipping the narrative. Today, oil is the ugly duckling.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to LWS Financial Research to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.