Disclaimer

LWS Financial Research is NOT a financial advisory service, nor is its author qualified to offer such services.

All content on this website and publications, as well as all communications from the author, are for educational and entertainment purposes only and under no circumstances, express or implied, should be considered financial, legal, or any other type of advice. Each individual should carry out their own analysis and make their own investment decisions.

Beyond the model portfolio, we will use it as a starting point to share in this weekly bulletin some classic value stocks that we find attractive to study and monitor, with the dual aim of being educational and illustrating our investment philosophy and analytical methodology. To launch this new section, we bring you $FDS.

FactSet is one of those businesses that falls into the category of “invisible infrastructure” of financial markets. It doesn’t make headlines like Nvidia or Microsoft, but it is an operational pillar for much of the investment industry. Its value proposition is to provide financial data and analytical tools through a subscription model, with high margins and a level of recurrence that many software companies would envy.

The core of the business remains its desktop platform—the more agile and customizable equivalent of a Bloomberg Terminal—but recent growth has come from enterprise services: data feeds, APIs, cloud solutions, and workflow management for banks, asset managers, or private equity funds. This allows FactSet to capture clients who are not only looking for research or portfolio monitoring, but also data integration into internal processes, regulatory compliance, or reporting.

Weekly macro summary

There have been quite a few interesting events to analyze this week, and below I list the most noteworthy news. Let's get started:

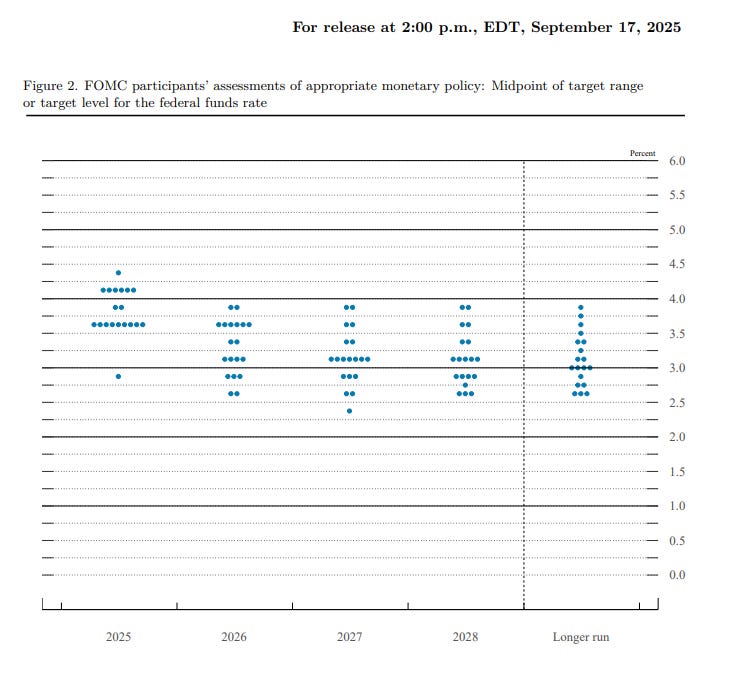

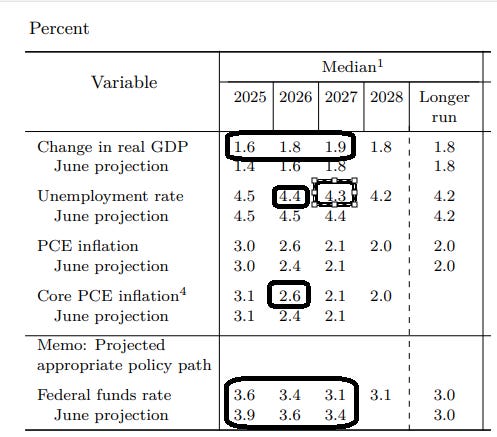

The Federal Reserve has cut rates by a quarter point and signaled further reductions for the remainder of the year, marking a clear shift in its official stance: inflation is no longer the main enemy, but rather the deterioration of the labor market. Powell, though neither excessively hawkish nor dovish, made it clear that risks now tilt toward a rise in unemployment, and any additional weakness in jobs could trigger a negative spiral. The new dot plot (members’ expectations for the path of interest rates) suggests we will see two more cuts before year-end, bringing rates to the 3.5%–3.75% range by the end of 2025. This adjustment looks like an attempt to slow economic deceleration without assuming that inflation is fully under control—indeed, projections still point to year-end inflation at 3%, far from the 2% target, which now seems relegated.

What matters most is not the cut itself, but the change in tone within the FOMC. Until recently, much of the committee had insisted on keeping rates higher for longer. Now, even usually hawkish figures like Waller and Bowman—both Trump appointees—have voted in favor of this cut and the new pace of easing. Only Miran, newly arrived on the board and closely aligned with the White House’s expansive fiscal stance, called for an even larger cut of 50 basis points.

This shift coincides with a labor market that is beginning to show clearer signs of fatigue: weak hiring, falling hours worked, and a noticeable slowdown in net job creation. Powell’s message, though wrapped in technical language, was straightforward: if employment keeps weakening, the Fed will not hesitate to keep cutting rates, even if inflation has not yet fully converged. It marks a shift in priorities, confirming what some have long argued—that the focus is no longer on squeezing out residual inflation but on preventing a deeper economic slowdown. The most interesting part was not the rate decision itself, but the upgrade in projections for real GDP growth, unemployment, and a slight uptick in inflation, signaling that the Fed expects the economy to run hotter next year.

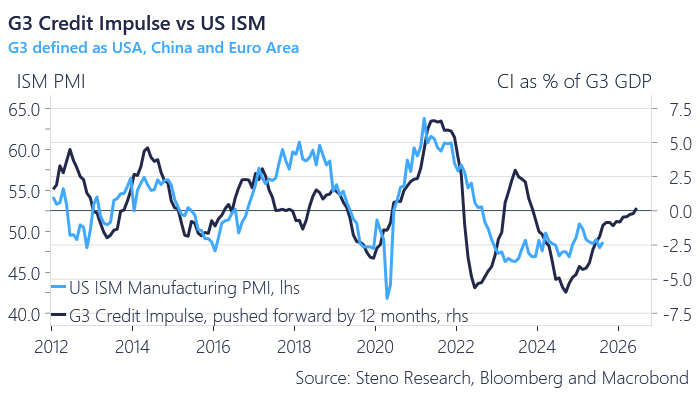

Looking at other indicators, such as credit impulse or retail sales—which continue to surprise to the upside—the negative narrative about the U.S. economy fades, and the possibility of a reacceleration, rather than a slowdown, emerges strongly, aligning much better with the Fed’s expectations.

The political pendulum has swung hard in the opposite direction, definitively abandoning DEI and ESG. The suspension of Jimmy Kimmel Live after comments about the assassination of Charlie Kirk illustrates just how far U.S. politics is entering dangerous territory for free speech (albeit in a miserable form). The chain reaction—threats from the regulator, pressure on broadcasters, and the immediate withdrawal of the show—shows how the line between institutional oversight and political censorship is blurring. Trump openly celebrated the move while calling for the punishment to be extended to other critical hosts. The response of media groups such as Nexstar or Sinclair does not appear unrelated to their need to maintain good standing with the FCC amid sensitive regulatory processes. And here lies the key point: when regulatory compliance becomes a political weapon, media independence erodes.

Beyond the partisan noise, the message sent to the media ecosystem is clear: speaking “off script” can cost you your job. We’ve already seen academics, journalists, and commentators fired for describing Kirk in less-than-flattering terms. This climate of fear works to Trump’s advantage, disciplining public discourse and placing the press under constant threat of sanction or litigation.

The signal for investors is that the winds have shifted, and fund positioning and capital flows will shift as well. Our thesis years ago was precisely this: that ESG, DEI, and the capital misallocation driven by those principles (seeking politics rather than returns) would eventually reverse. We are now there, and this is only the beginning.

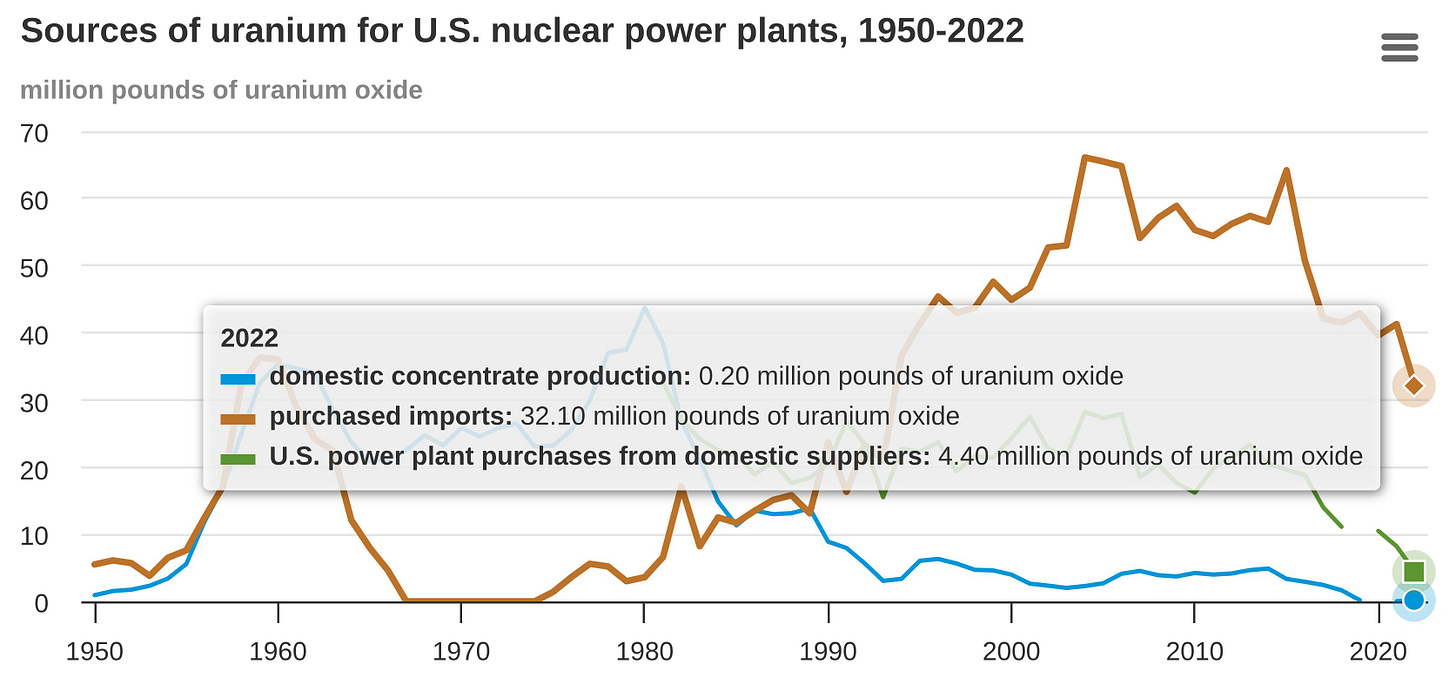

In a context increasingly defined by the politicization of supply chains, the U.S. has begun to design a roadmap to break its dependence on Russian enriched uranium, which currently covers 25% of the needs of its 94 operating reactors. This is no minor task, given that about 20% of the country’s electricity depends on those facilities. The logic is simple, though uncomfortable: if Russia were to cut supply tomorrow, roughly 5% of the U.S. energy matrix would vanish.

The Trump administration, reviving an initiative launched in 2020, has reactivated the debate over creating a strategic uranium reserve, with the dual aim of securing supply and sending a clear signal of support for nuclear energy as a pillar of future electrification. Energy Secretary Chris Wright made it clear this week that the goal is twofold: to progressively eliminate Russian imports and significantly expand domestic enrichment capacity. But the path is long, as domestic production is practically zero and has plummeted over the last decades.

Today, the U.S. has only two commercial enrichment facilities: the Urenco plant in New Mexico—European-owned—and a small facility in Ohio (Centrus Energy), which is only just beginning to produce fuel for advanced reactors. Meanwhile, China holds reserves equivalent to 12 years of demand, and the EU, 2.5 years. The U.S., by contrast, has barely 14 months of coverage. Moscow has already responded by limiting its exports to the U.S., yet another sign that uranium, much like natural gas a few years ago, has ceased to be just another commodity and has become a geopolitical weapon.

What matters here is not only the energy question but the industrial transformation underway. The U.S. wants to reindustrialize its nuclear fuel chain, seeking to attract private capital into a sector historically dominated by public or quasi-public entities, given its civil–military duality. The underlying question, however, remains unanswered: to what extent can the private sector shoulder the costs, risks, and timelines that this process entails? The nuclear industry is not Silicon Valley, and the margin for error is nonexistent. But if the goal is to accelerate the energy transition without depending on hostile actors, uranium (and its refining) must return to the radar of any serious energy analysis. The U.S. is, at last, acting accordingly. Whether it will be in time remains to be seen.

Donald Trump has once again put one of his most persistent regulatory obsessions back on the table: eliminating the requirement to publish quarterly earnings. In a recent Truth Social post, the president suggested that companies should move to a semiannual reporting scheme, which, according to him, would allow managers to focus more on the business itself and less on the accounting narrative every three months. The proposal is not new, but now, with a Republican-majority SEC (3–1), it once again has real political traction.

Formally, the change would not require going through Congress. A majority vote within the SEC would suffice, which, given the current composition, seems plausible. Even so, the process could take 6–12 months and is not free from internal resistance, since although the SEC follows executive guidance, it has historically maintained a certain degree of independence. The idea of abandoning quarterly reporting is not exclusive to Trump. Back in 2018, Warren Buffett and Jamie Dimon criticized the harmful effects of quarterly “guidance,” though they did not call for eliminating earnings reports altogether. Their argument was that accounting short-termism penalizes strategic investment and discourages structurally valuable decisions. But removing guidance is one thing; extending reporting periods to six months, as Trump proposes, is another matter entirely. Different league.

Trump’s geopolitical argument—that China has a 50-year business vision while the West is trapped in “quarterly capitalism”—is, at best, inaccurate. Chinese companies also report quarterly, in some cases under stricter standards. Perhaps the closest model to Trump’s proposal is the UK and EU, where only semiannual reporting is required. But the size, dynamics, and sophistication of U.S. markets make the comparison of limited relevance.

In my view, we are in an extremely speculative market phase, driven by expectations around technology and artificial intelligence that are detached from underlying economic reality, as has happened in past cycles. In fact, if we look at the weight of tech stocks versus more defensive sectors (and although it’s reasonable for that share to grow over time), we are already approaching 40% of total market capitalization—disproportionate relative to their cash generation.

This is an environment where every headline and event has an outsized impact on stock prices, and noise replaces signal. What matters most in such conditions is keeping a cool head and sticking to our discipline and investment style.

Amid the constant devaluation of fiat money—now in an accelerated phase—it becomes essential to invest in real assets, at the very least to preserve purchasing power. This Cantillon effect, which widens the gap each day between investors (Wall Street, even in its retail version) and Main Street, is becoming increasingly visible, as the chart above illustrates. Position accordingly.

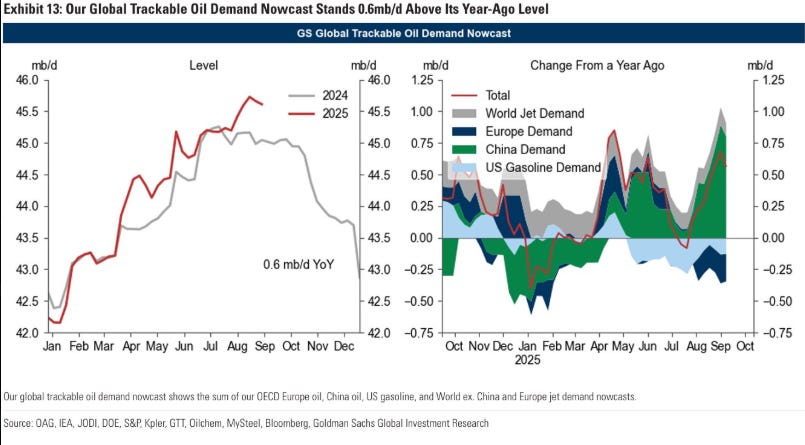

Paradoxically, for the depressed sentiment surrounding the space—which the data stubbornly contradicts—the IEA is backtracking and adjusting its forecasts to what has actually been observed, marking a political shift in the agency. Starting with demand, we can see that, far from catastrophic figures, even taking only OECD + China data (excluding India, Africa, or APAC, which are growing much faster), we are comfortably above last year, and China’s demand, often underestimated, may remain strong, even if only to build inventories by taking advantage of attractive prices. So much so that the IEA is already retracting what it claimed just a few months ago, now acknowledging that the demand peak is still far away. Oil still has a long runway.

Oil demand is growing by more than one million barrels per day of incremental demand each year. I worry more about where that oil will come from in the next five to ten years.

— Chris Wright, Secretary of Energy

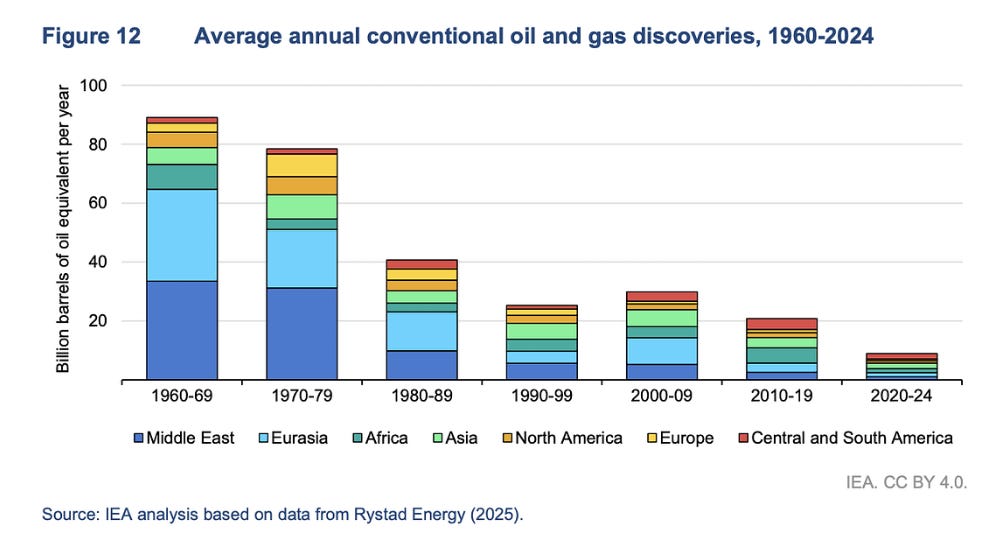

As we saw in G&R’s Q2 commentary, as much as analysts’ projections point to a large oil surplus, the signals we should be seeing in margins and inventories are not materializing and do not support these forecasts. What was most interesting, however, were their projections on decline. The energy outlook drawn from those data is striking: the world is facing a structural erosion of its fossil production base, even with sustained investment. The observed decline after the peak of conventional fields is 5.6% annually in oil and 6.8% in gas, figures that hide key heterogeneity, since large fields resist better (2.7%), while small ones collapse (11.6%). Geography and technology also make a difference, with the Middle East losing only 1.8% annually, while Europe is close to 10%; in deepwater, the depletion rate exceeds 10%, more than double that of onshore.

If we move to the terrain of “natural decline”—the loss of production without compensatory investment—the picture is even more severe: 8.5% for crude and 9.5% for gas, equivalent to losing 5.5 million barrels per day and over 26 Bcf/d every year. In practice, almost the entire production of Saudi Arabia disappears from the global map every three years.

As if this weren’t enough, developing a new conventional project from license to first production already takes close to 20 years. This means that the window to respond to structural deficits has narrowed dangerously. The cost of sustaining supply at current levels is estimated at about $540 billion annually, and by 2025 investment will hover around $570 billion. Thus, since 2019, roughly 90% of upstream capex has gone simply to slowing decline, not to increasing net capacity.

The growth of conventional supply is exhausted, and most of the capital only serves to keep us in the same place. This leaves the industry structurally dependent on new production hubs—deep offshore, shale, LNG—which are not free from geological, financial, and political constraints. If the data holds, the tension between natural decline and defensive capex will be one of the central catalysts of the next commodity bull cycle, as already noted in some analyses by Goehring & Rozencwajg and in our own deep dives.

Looking at the major discoveries since the 1960s, we see how the trend is clearly downward, especially in OPEC, whose vast fields are not infinite and suffer the same decline and depletion as the rest of the world. The day OPEC+ disappoints, the shock will be enormous, and it is a mathematical certainty that it will come.

Model Portfolio

The model portfolio's return is +18.59% YTD compared to +0.74% for the S&P500 (S&P in €), and +98.7% versus +44.57% for the S&P500 since inception (September 2022). The model portfolio, as of Friday's close, is as follows:

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to LWS Financial Research to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.