Disclaimer

LWS Financial Research is NOT a financial advisory service, nor is its author qualified to offer such services.

All content on this website and publications, as well as all communications from the author, are for educational and entertainment purposes only and under no circumstances, express or implied, should be considered financial, legal, or any other type of advice. Each individual should carry out their own analysis and make their own investment decisions.

Weekly macro summary

There have been quite a few interesting events to analyze this week, and below I list the most noteworthy news. Let's get started:

The meeting between Trump and Putin in Alaska has produced the first tangible draft for a possible resolution of the conflict in Ukraine. The details that have emerged outline a framework with profound implications both geopolitically and economically. Russia would be willing to return small occupied portions in the north (Sumy and Kharkiv), of little strategic value, in exchange for tacit recognition of full control over Donetsk, Luhansk, and Crimea. In return, it would freeze the front in Zaporizhzhia and Kherson without giving up positions. In addition, Ukraine would be required to renounce NATO membership and accept security guarantees not explicitly tied to NATO’s Article 5. The framework would also include a clause guaranteeing the official use of the Russian language and the free functioning of the Orthodox Church aligned with Moscow.

From the Russian perspective, the proposal acknowledges its military failure on the southern front and seeks to consolidate the gains achieved in Donbas. For Trump, the move is strategic: it offers a resolution framework that allows him to present a diplomatic victory without deploying forces or increasing costs for the U.S. Ukraine, for its part, has already rejected any territorial concessions that legitimize the occupations (though it will eventually be forced to accept them). In practice, the proposal implies accepting the partition of the country in exchange for vague guarantees, in a context where it continues to endure daily attacks from Russian drones and missiles. The economic implications are also significant. The possibility of freezing the conflict—even without resolution—would reduce geopolitical risk in Eastern Europe, directly impacting risk premiums, the energy market, and, to a lesser extent, agricultural commodities. Some countries could interpret the initiative as a pathway to normalize trade relations with Russia and push for a partial lifting of sanctions.

For the first time since 2022, the partition of Ukraine is being openly negotiated, albeit under external pressure. What for Moscow represents an orderly retreat, for Washington could be a narrative victory.

For decades, the dominant narrative has been that technological progress, while destroying jobs in the short term, always ends up creating new sectors to reabsorb displaced labor. But there is growing evidence that this story, at least in the case of developed economies, is no longer holding true. Since the 1980s, the U.S. labor market has been destroying more jobs through automation than it creates. And most worrying of all, the destruction no longer affects only manual or repetitive work, but also technical, administrative, and professional functions—precisely those once thought to be protected by their cognitive complexity.

Advances in AI only accelerate this process. The frontier is no longer strength, but intelligence. And if a machine can think—or rather, efficiently simulate thinking—the economic incentive to substitute human labor with capital is unbeatable. The productivity logic leads to the paradox of irrelevance: producing more with fewer people sounds good… until you realize those people are also consumers. Without wages there is no demand, and without demand the model collapses. The logical consequence would be structural deflation, with the State once again forced to intervene as the stabilizer of last resort.

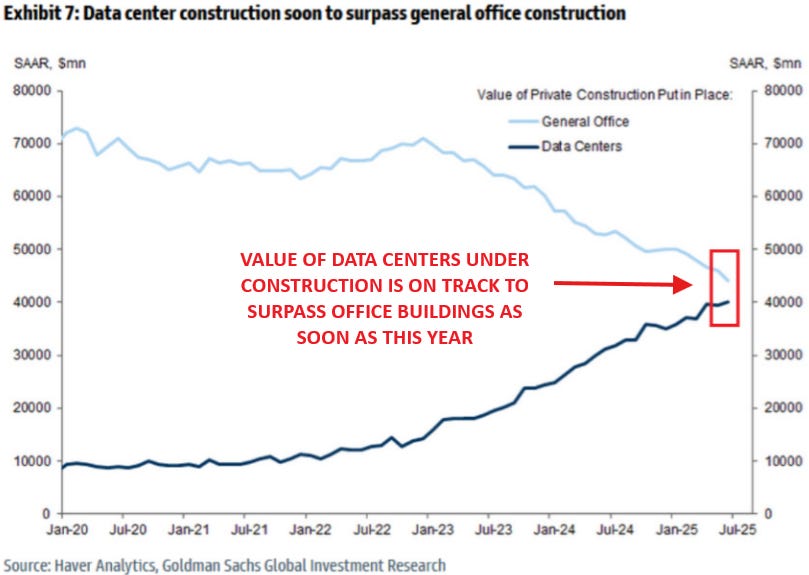

This week we shared a very interesting article by Kuppy, which questions the rationality of current AI investment given the poor prospects for satisfactory returns that this CapEx cycle offers. It transforms the nature of extraordinary businesses (big tech—the best companies in history) into a highly capital-intensive industry, much like what happened in the early 2000s. In this sense, this year, and for the first time in history, spending on data centers will surpass spending on general-purpose office buildings. A sign of the times.

Powell spoke at Jackson Hole and, as he usually does, he said nothing… and everything at the same time. In his remarks, he made it clear that the balance in the labor market is starting to crack—though he called it “a curious balance”—with a simultaneous slowdown in both supply and demand. And when that happens, surprises tend to come quickly, and from the wrong side. The message was not particularly optimistic, but neither was it alarmist. More like an implicit warning: if the data allow, the door is open to rate cuts in September, without making any promises (the market is already pricing in a 90% chance of it happening). And here is where it gets interesting. Because despite acknowledging labor market cooling, Powell did not want to appear complacent about inflation, still far from the 2% target and now exposed to new pressures via tariffs. According to the Fed, the impact should be limited and temporary—but, as always, the “transitory” tends to be stickier than the models predict. That’s why the language remains ambiguous, but the direction is clear: with policy already in restrictive territory and growth losing steam, the question is no longer if there will be a cut, but when and how deep.

The market, as usual, heard what it wanted. The odds of a September cut jumped from 75% to 90% in minutes. Wall Street rallied, the dollar fell, and bonds celebrated as if the cut were already signed. But it’s not. Everything depends on the September 5 jobs data and the CPI/PPI the following week. Only if both confirm economic moderation will the FOMC make a move. In this context, what the Fed says matters less than what the data say—and what Trump thinks weighs more than what the models project. To me, the most relevant message was about the inflation target, which we’ve known for some time is the hinge needed to accommodate the massive debt load. Powell hinted that the 2% is no longer set in stone, but rather an aspirational goal… where he once said 2%, he now means 3%.

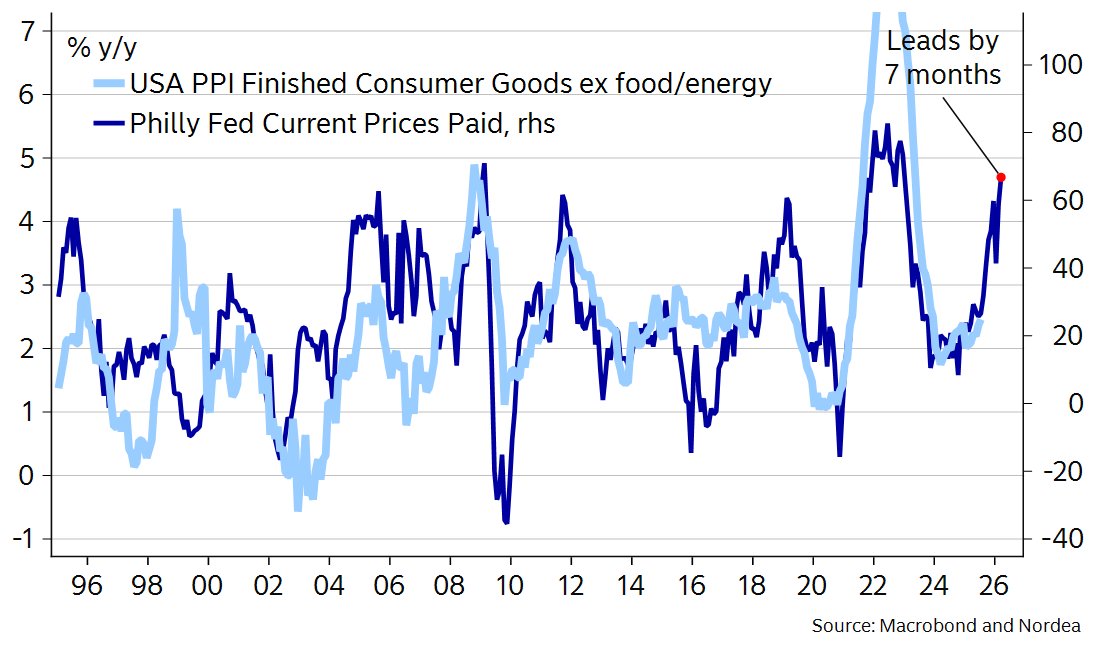

The Fed still expects tariffs to eventually translate into higher inflation, and there are good reasons for that. If we haven’t seen this effect yet, it’s because companies front-loaded their orders, but these inventories are running out and, according to leading indicators, we’re about to see the consequences of trade barriers.

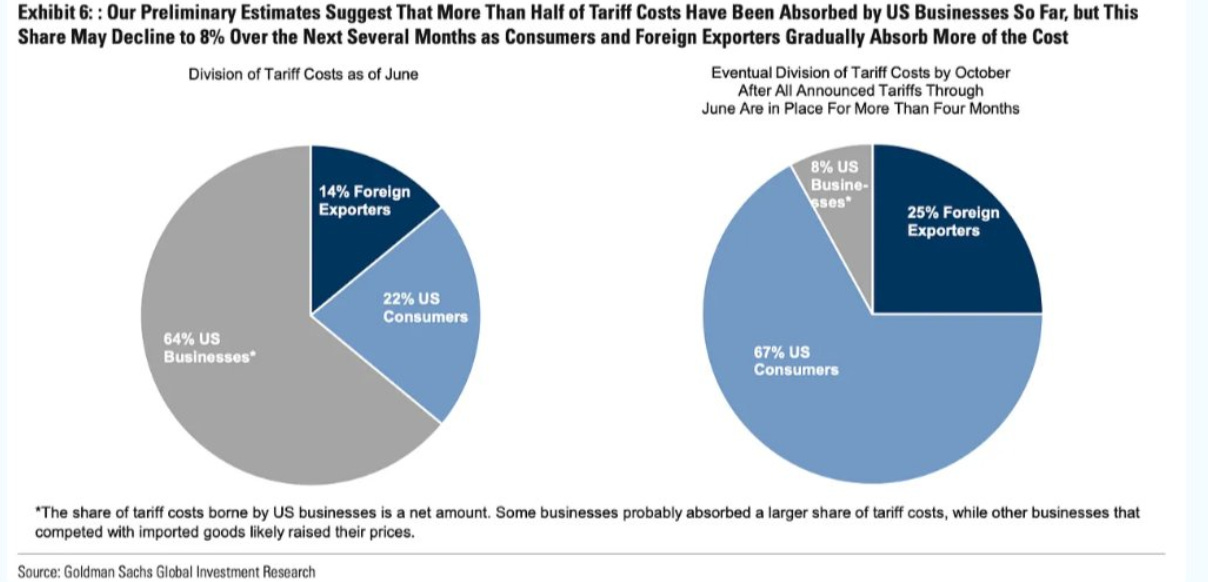

Not only that, but for now, companies are absorbing 64% of the additional costs—but this has a limit (and should also impact margins and valuations). Most likely, all—or at least the majority—will eventually be passed on to the consumer.

The Trump administration is planning a controversial but strategically coherent move: to redirect $2 billion from the CHIPS Act—originally intended for semiconductor research and manufacturing—toward mining and processing projects for critical minerals such as germanium, gallium, or lithium. The goal: to reduce dependence on China for raw materials essential to defense, the energy transition, and the semiconductor industry itself. From a strategic standpoint, this reframing has a certain logic. Although Trump has labeled the law a corporate giveaway, his new version seeks to leverage funds already authorized by Congress to boost U.S. mineral sovereignty without going through another legislative round.

In parallel, and less visibly, there are also plans to use these funds to take direct equity stakes in companies in the sector, not just to finance CAPEX through subsidies. This would radically shift the logic of public intervention: from subsidies to co-investment. As for companies and sectors, potential beneficiaries range widely—from miners like Albemarle, which has already warned it will not build its lithium refinery without federal support, to recycling and intermediate processing firms, an area where the U.S. has lagged far behind. As China has shown, competitiveness and returns are no longer the primary driver of investment decisions, but rather the long-term interests and strategic goals of the nation. In another move in the same direction, the United States has confirmed its intention to start stockpiling a strategic cobalt reserve. The age of commodities thus begins its reign.

The pendulum swings back, and the greatest capital missalocation in history comes to an end. The U.S. administration has once again made it clear that its crusade against renewables is not symbolic but operational. In his latest Truth Social post—the new American Official Gazette—Trump declared that his administration will not approve new solar or wind projects, dismissing them as farmland destroyers and the ultimate example of “stupidity.” And, as always, there is no ambiguity in his message: The days of stupidity are over in the U.S.

The declaration comes after the tightening of the federal permitting process, which is now centralized in the office of Interior Secretary Doug Burgum. A move that eliminates any pretense of technical neutrality: what used to be a routine procedure now requires political approval. And with Trump in crusader mode, companies in the sector are already bracing for the worst.

The rhetoric aligns with the facts. The One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA) is gradually eliminating production tax credits (PTC) and investment tax credits (ITC) for solar and wind until their disappearance in 2027, precisely when the power system most needs new sources. At the same time, tariffs on steel and copper—two key inputs for these technologies—have driven up development costs. While electricity demand soars, particularly in areas like the PJM grid (13 states across the East and Midwest), supply is contracting due to the progressive closure of coal plants and now the difficulty of adding renewables. The bet on nuclear is clear and determined, but the time it will take to come online may not match the pace of demand growth.

The official narrative blames renewables for rising prices—ignoring factors such as the surge in industrial demand from AI or the accelerated retirement of firm baseload capacity without equivalent replacement. But in practical terms, this policy creates an energy bottleneck with lasting inflationary consequences.

We are, essentially, facing an energy policy defined by exclusion: no renewables, no coal (due to economic infeasibility), no new nuclear in a reasonable timeframe… and yet, promises of manufacturing reshoring, AI growth, and massive electrification. The arithmetic doesn’t add up.

When we see a chart like this, our alarms and opportunity detectors go off. Speculative bets on oil are at 16-year lows, which makes little fundamental sense, and from a technical standpoint leaves little room for further downside (a mean reversion is always more likely).

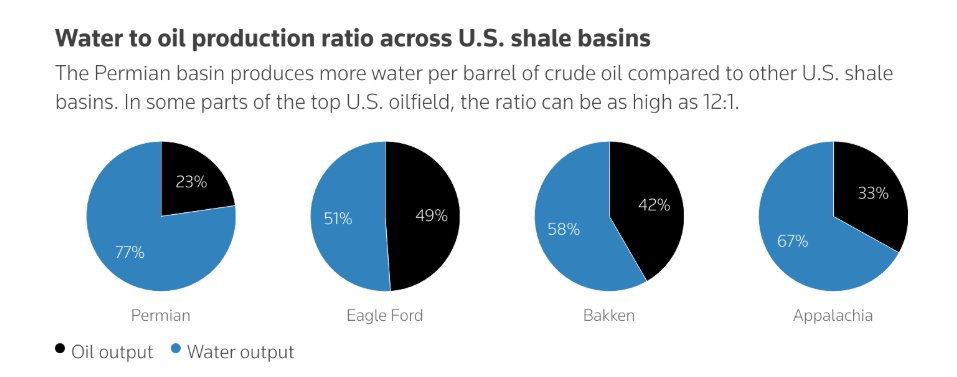

As we have often pointed out, one of the pillars of the bullish oil investment thesis is the collapse of growth in U.S. shale, which has been the only source of non-OPEC growth over the past decade. The data supports this view. In the chart below, we can see how the water-to-oil ratio in the Permian and other shale basins has already reached 50%, while the gas-to-oil ratio is also rising. Both metrics are indicators of geological deterioration, which will eventually translate into an inability to grow production (except if we see prices above $100, which would already validate the bullish thesis).

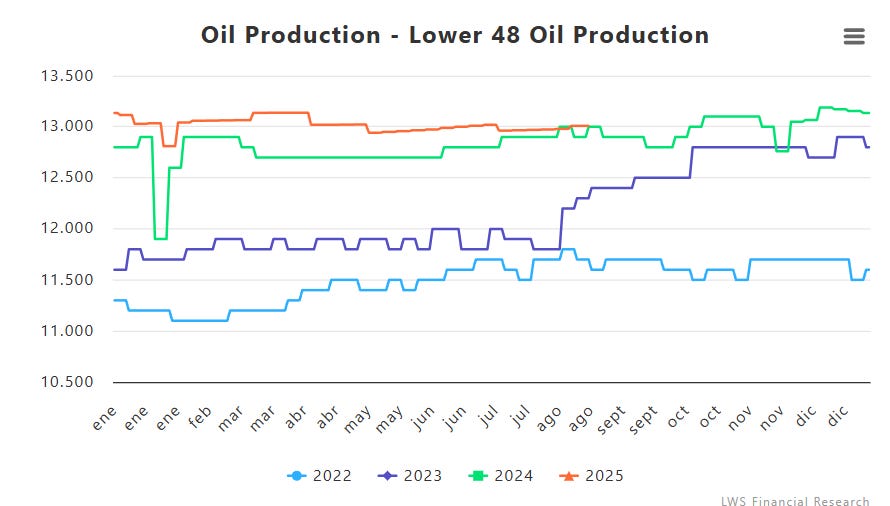

Looking at U.S. oil production figures, we see that there has been no effective growth this year, and since late 2024 production has in fact declined. This is only the beginning.

Model Portfolio

The model portfolio's return is +13.53% YTD compared to +10.38% for the S&P500 (our portfolio mesured in € terms, which is weighting -14% in our portfolio this year vs the S&P in $), and +90.3% versus +59.6% for the S&P500 since inception (September 2022). The model portfolio, as of Friday's close, is as follows:

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to LWS Financial Research to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.